TCIP - Turkish Catastrophe Insurance Pool

- CATRisk Consultants

- 1 dic 2020

- 17 Min. de lectura

Actualizado: 4 mar 2021

International Experience with Catastrophe Funds

Overview: In 2019 Turkey was the number 19 economy in the world in terms of GDP (current US$), the number 29 in total exports, the number 26 in total imports, the number 0 economy in terms of GDP per capita (current US$) and the number 41 most complex economy according to the Economic Complexity Index (ECI) Exports: The top exports of Turkey are Cars ($12.7B), Refined Petroleum ($6.63B), Delivery Trucks ($4.99B), Jewellery ($4.98B), and Vehicle Parts ($4.93B), exporting mostly to Germany($16.8B), United Kingdom ($12.1B), Iraq ($10.2B), Italy ($10.1B), and United States ($9.45B). In 2019, Turkey was the world's biggest exporter of Raw Iron Bars($2.77B), Hand-Woven Rugs ($2.14B), Wheat Flours ($1.05B), Hot-Rolled Iron Bars ($1.03B), and Marble, Travertine and Alabaster($870M) Imports: The top imports of Turkey are Gold ($11.5B), Refined Petroleum ($9.92B), Crude Petroleum ($6.55B), Vehicle Parts($5.72B), and Scrap Iron ($5.19B), importing mostly from Germany ($21.2B), China ($18.2B), Russia ($16.4B), United States($10.4B), and Italy ($9.4B). In 2019, Turkey was the world's biggest importer of Scrap Iron($5.19B), Non-Retail Synthetic Filament Yarn ($1.62B), Sunflower Seeds ($515M), Bran ($269M), Jute Yarn ($208M) Location: Turkey borders Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bulgaria, Georgia, Greece, Iran, Iraq, and Syria by land and Cyprus, Egypt, Romania, Russia, and Ukraine by sea.

Actual experience has shown that mounting uninsured losses from natural disasters presses governments in disaster-prone countries and regions to find practical solutions for catastrophe risk management and spurs the formation of national and regional catastrophe insurance programs. The Turkish government, with the help of the World Bank, investigated numerous national catastrophe risk management programs operating successfully in eight countries. The underlying rationale for these programs has been to address the challenges faced by the private insurance markets in insuring the risk of natural disasters. Table A2.1 lists the most well known of these programs. They include the Florida Hurricane Catastrophe Fund (FHCF), the California Earthquake Commission (CEA), the New Zealand Earthquake Commission (EQC), CatNat in France, the Taiwan Residential Earthquake Insurance Pool (TREIP), and the Japanese Earthquake Reinsurance Company (JER).

Source of Seismicity in Turkey

Most earthquakes in Turkey are a result of tectonic movement. The bulk of the Turkish landmass is located on the Anatolian plate, which is caught by the major Eurasian, Arabian, and African plates, respectively. The northward movement of the latter plates against the relatively stable Eurasian plate squeezes the Anatolian microplate westward along the northern Eurasian plate. Earthquakes result from the ensuing collision along the North Anatolian Fault zone. Similar in dimension and activity to the San Andreas Fault, the zone constitutes the northern boundary of the Anatolian plate. The south-eastern boundary of the microplate is formed by the northeast-trending East Anatolian Fault, which joins the more eminent northern fault. The horizontal movement of the Anatolian and Eurasian plates against one another creates a pressure build-up over a long period that can be relieved only through earthquakes. These often simultaneously transfer pressure to other points in the fault system. Frequently, earthquakes along the Anatolian fault system originate near the surface, which makes them more intense and devastating.

Economic Damage of Turkish Earthquakes

The economic cost of natural disasters to Turkey has been severe to the economy. The expected annual economic stock loss from earthquakes in Turkey is estimated to be US$100 million. Of more importance, however, is the probable maximum economic loss from a single or several catastrophic events, which can be many times the expected annual loss (table 1.2). The cost of a 1-in-200-year event (an event with a 0.5 percent annual exceedance probability) is likely to be greater than $11.4 billion, or 6.2 percent of the country’s GDP. The cost of a more frequent 1-in-20-year event (an event with a 5 percent annual exceedance probability) is likely to exceed $3.5 billion. This potential severity suggests the inherent limitations of the average-cost budgeting approach to natural disasters adopted by many governments shows the importance of catastrophe risk transfer programs such as the Turkish Catastrophe Insurance Pool (TCIP).

Recent modelling work indicates that the Istanbul and Izmir regions are in the path of the western progression of earthquakes along the North Anatolian Fault. Furthermore, although there is some diversification of commerce and industry toward the eastern regions, the Istanbul metropolitan area easily represents the peak seismic risk accumulation in Turkey, because it accounts for over one-third of the national GDP (World Bank 2000). The issue of Istanbul’s population increase (from 7.3 million in 1990 to an estimated 12 million in 2006) and the settlement of new inhabitants built, in uninsurable buildings.

The earthquake coverage was offered with a 20 percent coinsurance of loss and a 5 percent deductible; premium rates were subject to a high reinsurer-driven tariff.

From the financial sector’s perspective, provision of earthquake coverage by private insurers was untenable, because so few people had purchased the coverage and because the industry’s earthquake reserves were dangerously low. As of December 31, 1997, Turkey’s total accumulated industry earthquake reserves were approximately $24 million. By contrast, the annual fire and engineering premium income, the greater part of which was earthquake related, was $140 million. Given unfavourable tax treatment of earthquake reserves by Turkish accounting regulations and generous reinsurance exchange commissions available on catastrophe business written by local insurers, local companies found it considerably more profitable to cede most of the earthquake premium to foreign reinsurers (a move that did not require setting aside catastrophe reserves).1 In the absence of this reinsurance-based “washing” of earthquake premiums, two-thirds of all such premium income would have been set aside in catastrophe reserves by law.

Whether all nonlife insurers have a true understanding of their financial positions has been questioned. For example, claims incurred but not reported (IBNR) provisions were not required and, as a result of their nontax-deductible status, were not set aside. Thus, the industry was not operating on a fully funded basis. Premium receivables from agents and policyholders often were greater than the companies’ net assets. In other words, investment income was substantially lower than it would otherwise be, and insurers carried significant credit risk. The combination of these circumstances suggested that the private insurance industry was unlikely to increase catastrophe insurance penetration if left to its own devices.

Finally, a purely private sector approach to catastrophe coverage would have had to deal with the attempt of some insurers to underwrite only “good” risks, a tactic that would lead to coverage gaps in most disaster-prone areas, which usually have large concentrations of relatively poor people.

Despite the limited capital base, lack of underwriting expertise, and shortage of qualified personnel, the Turkish insurance industry clearly had the technical potential, both in terms of reinsurance expertise and distribution capabilities, to develop a nationwide catastrophe insurance program. Although the total excess of loss reinsurance capacity allocated to Turkey by the global reinsurance market was small—$800 million, compared with, for example, $2.4 billion for Mexico—the Turkish government and the World Bank believed that this amount could be significantly increased. After discussions with international reinsurers, they formed the view that, given a more efficient approach to underwriting and pooling of insured catastrophic risk by the Turkish insurance sector, the international reinsurance markets would be prepared to provide substantial additional capacity to support greater penetration of catastrophe insurance in Turkey. In global terms, Turkey historically had been allocated a fraction of 1 percent of available capacity; therefore the scope to increase the proportion of registered properties insured for earthquakes through private markets was substantial.

Marmara Earthquake

The Marmara earthquake dealt a heavy blow to Turkey not only in loss of life but also in direct economic damages. Most severely affected was the expansive area around Izmit Bay, including the four districts of Kocaeli, Sakarya, Bolu, and Yalova. The industrial heartland of Turkey, this region contributes more than 7 percent of the country’s GDP.

The Marmara earthquake severely affected Turkey’s economic infrastructure, enterprise sector, social infrastructure, and financial systems. The energy, transport, and telecommunications sectors were particularly hard hit because of their high concentration near the epicenter. In addition to countless kilometers of underground cables that were destroyed or damaged, 3,400 electricity distribution towers and 490 kilometers of overhead cables were affected. Damage to refineries and pipelines led to environmental damage and required massive repair to both the structures and the ecosystem. Losses from fire damage were only partially covered by existing fire-after-earthquake insurance.

The Gebeze-Izmit-Arifye railroad and a major rail factory in Adapazari were devastated, as were ports and jetties in the area. The State Planning Organization estimated that $600 million would be required to restore these sites.

The indirect economic impact on the private sector was significant. Small enterprises were affected more than larger enterprises. Microenterprises comprised most of the 15,000 businesses (many first-floor shops) that were physically destroyed and the 31,000 businesses that were damaged.

The indirect impact on the financial infrastructure resulting from the quake was also material. Losses arising from uninsured damage resulted in many nonperforming loans: total exposure of public banks in the region was estimated to be $119 million. Cash loans outstanding of private banks in the region were estimated to total $614 million. As of 1999, deferred schedules and reduced interest rates were being granted; the total expected amount of restructured loans is $56 million, with $42 million in additional subsidized credits.

Although estimates of overall economic losses from the Marmara earthquake vary significantly, both direct and indirect losses were clearly severe, totalling billions of dollars and amounting to up to 5 percent of GDP.

Marmara Earthquake Emergency Reconstruction Project

The framework consisted of investments in the physical reconstruction of damaged infrastructure and buildings, in social and economic recovery, and in emergency preparedness, disaster mitigation and planning, and risk financing. The World Bank funded $505 million for the Marmara Earthquake project loan; donors contributed an additional $1,290.75 million. Of the $505 million provided by the World Bank, $123 million was allocated to the Disaster Insurance Scheme, under which $100 million in initial capital support went to the insurance pool through an uncommitted contingent loan facility and $23 million went to technical assistance. The World Bank also took the lead in technical assistance to the Turkish Treasury’s General Directorate of Insurance (GDI) to design a catastrophe insurance pool for Turkey.

The Turkish Catastrophe Insurance pool, TCIP was created:

It was designed to (1) be compulsory for all homeowners, (2) to offer coverage affordable for most Turkish homeowners, (3) to be a true risk transfer program, (4) to have sufficient claims-paying capacity to materially limit the government’s fiscal exposure to catastrophe risk, (5) to be able to build national catastrophe reserves over time, (6) encourage mitigation through risk-based premium rates and other venues, and (7) rely on the distribution and claims settlement capabilities of the Turkish private insurance market.

The government articulated the following core objectives for the TCIP scheme:

• Provide affordable and effective basic earthquake insurance coverage to all registered urban dwellings on a compulsory basis.

• Over time, build a fund capable of paying all but the most catastrophic insured losses from its reserves and reinsurance.

• Achieve financial sustainability in the long run, thereby reducing the government’s obligation to provide post disaster emergency relief to the owners of the registered Turkish housing stock.

• Provide strong incentives for ex-ante mitigation, including improvements in the enforcement of the construction code, and thereby promote safer construction practices.

Compulsory earthquake insurance offered by the TCIP is sold separately from comprehensive householder insurance (a stand-alone product). Because 100 percent of risk written under the TCIP was to be transferred to the program, the government decided that every insurance company with a valid license, and regardless of its perceived capital strength, would be authorized to sell earthquake policies on behalf of the TCIP.

Insurance companies are required to pass on certain information about insureds and to collect and pay premiums, net of commission, to the TCIP in a timely manner. Their commission originally was set at 12.5 percent but one year later was increased to 17.5 percent in areas outside Istanbul to increase penetration in the less-disaster-prone parts of the country.

The TCIP fully collateralized its policy sales to reduce credit risk exposure to the insurance industry. This process required every participating insurance company to post a deposit of $50,000 with the TCIP.

World Bank

Since the program’s launch, the World Bank has provided capital support to the TCIP through a contingent investment loan. This loan reduces reinsurance costs, which speeds accumulation of the pool’s capital reserve fund, and serves as part of the pool’s overall claims-paying capacity in the event of a major disaster. The loan is due to be closed in October 2006 (a 14-month extension was granted at the request of the Turkish government). It was increased at the end of 2003 from $100 million to $180 million, an action that will increase the relative growth rate of the reserve fund in the future, assuming no major disaster occurs.

Earthquake Insurance Coverage Terms and Conditions

At the end of 1999, and nine months before creation of the TCIP, Turkey had slightly more than 600,000 earthquake policies in force through private nonlife insurers. Penetration was only 4.6 percent of the qualified market, primarily because catastrophe insurance coverage was offered as an optional endorsement to the homeowners (fire) policy. In effect, this arrangement limited the number of earthquake policies to the number of in-force primary fire polices. Although the bundling of natural hazards covers with fire policies is a common insurance practice with many advantages, it has one important disadvantage. By combining the two covers and selling them as a package to the consumer, an insurer makes catastrophe coverage subject to considerably higher affordability constraints. In practice, only better-off homeowners, a small market segment, can afford catastrophe insurance.

To remove affordability constraints, the government decided that the TCIP would offer stand-alone earthquake insurance coverage that would be marketed separately from the fire policies offered by private insurers.7 The growth of catastrophe insurance coverage in Turkey no longer would be limited by the general growth of property insurance penetration, which is highly correlated with the country’s GNP. This design feature sets the TCIP apart from many of its peer programs in other disaster-prone nations. For instance, the earthquake cover offered by the California Earthquake Authority is made available as an optional endorsement to the homeowner’s policy and cannot be bought separately. In the case of France’s Cat-Nat and New Zealand’s Earthquake Commission (EQC), catastrophe coverage also is linked to the purchase of underlying fire policies, making it highly dependent on the level of overall household insurance penetration. In France and New Zealand, property insurance penetration is well over 90 percent (although, in industrialized countries, underinsurance is an ongoing problem).

TCIP Insurance Contract Characteristics

The TCIP policy offers coverage on a first-loss basis, meaning that it does not impose underinsurance penalties when the value of a dwelling is significantly higher than the limit of coverage obtained from the TCIP. The sum insured is calculated by multiplying the size of the dwelling in square meters by construction prices per square meter, which vary for different classes of construction.

Construction prices for all classes of construction are adjusted regularly with changes in the construction cost index published by the government. As of November 2004, the TCIP premium rates varied from 0.44 percent for a house built with a reinforced concrete and steel carcass located in earthquake zone 5, to 5.50 percent for a dwelling built with low-resistance material and located in earthquake zone 1 (table 2.4; earthquake zones are described below).

Unlike the CEA, which imposes a deductible of 10 percent, the TCIP applies a minimum 2 percent deductible to the sum insured to avoid “smallish claims” and reduce the pool’s administrative and reinsurance costs.

The TCIP must adjust premium levels when they fall behind inflation or are insufficient to cover operational costs. Since 2000, premium rates for construction type A (buildings made of a steel or reinforced concrete) have increased between 16 percent (zone 1) and 76 percent (zone 5). During the same period, rates remained flat for construction type B and decreased slightly for type C, which accounts for the smallest share of insured dwellings.

Risk Financing Strategy

The TCIP’s risk financing strategy optimizes the relationship among premium levels, policy coverage, and credit worthiness. The pool is estimated to be able to cover a 1-in-200-year event without becoming insolvent. Its objective is to achieve a solvency level that would enable it to survive a 1-in-250-year event at an acceptable confidence level. Although the program does not yet have a credit rating, its implied rating based on the overall amount of its claims-paying capacity is estimated to be BBB+ (S&P rating system).

EQECAT has developed a specific probabilistic earthquake risk model to determine the minimum amount of the pool’s claims-paying capacity and the required pure premiums. Using historic earthquake data and information about the location of insured properties and their vulnerability to earthquakes, the model produced an aggregate loss exceedance probability curve (AEP) that allowed quantification of maximum TCIP losses for a given return period, for example, 50 years.

Initially, because the program’s own reserves were low, Milli Re decided that the pool would retain just enough risk to be covered by the World Bank contingent capital facility; the rest would be transferred to the international reinsurance market. Contingent debt proved to be a useful instrument for financing catastrophe pool loss exposures, particularly in the first years of operation, when rapid buildup of surplus is required. The contingent capital facility provided by the World Bank also helped the pool to deal effectively with the fluctuations and cycles of the reinsurance market.

Reinsurance has been the main source of the TCIP’s claims-paying capacity from the beginning (table 2.5). To accommodate the growing number of homeowners participating in the program, the terms of the TCIP’s reinsurance agreement provided for the possibility of adding new layers of risk coverage in the course of an underwriting year.

The original design of the TCIP program envisioned no government financial commitment to the program. However, in a heated public debate, the government was accused of being financially irresponsible to prospective policyholders. Subsequently, it had no choice but to renounce its original intention to let the TCIP prorate claims in case of an earthquake causing insured losses in excess of the pool’s financial resources.

Since then, the government has become the pool’s reinsurer of last resort: the government would provide additional claims-paying capacity to the program if its funds are insufficient to meet all claims in case of a very large catastrophic event. However, there is no change in the Decree Law on this issue, so this guarantee must be seen as conditional. Today, with the TCIP’s overall claims-paying capacity approaching $1 billion, allowing the pool to absorb 1-in-200-year event losses, its contingent call on government financial resources has been somewhat reduced.

TCIP Reinsurance Tender

The pool’s approach to reinsurance buying has become considerably more sophisticated. To determine the optimal amount of reinsurance and the appropriate structure of the reinsurance program given affordability constraints, the TCIP evaluated the bids using a stochastic scoring model based on the TCIP earthquake model and a simplified dynamic financial analysis (DFA) model. DFA uses computer simulation techniques to project a company’s income and balance sheets through a multiyear period, typically 10 or 20 years. The scoring model estimates the probability of TCIP solvency for a one-year period, taking into account recoveries from a specified reinsurance program and the premium charged for such a program. The reinsurance program that received the highest score was selected for final negotiations. The TCIP’s reinsurance tender may have been the first instance of a stochastic model’s use to identify the most cost-effective reinsurance proposal for a major risk pool. Given the relatively unique competitive/cooperative nature of the reinsurance sector, only experts on reinsurance markets should apply such an approach.

The TCIP has consistently maintained a level of solvency that would make it highly likely to survive an earthquake in Istanbul with a 100-year return period. Although the amount of claims-paying capacity maintained by the pool has remained relatively stable, its composition has changed considerably (table 2.5). In the first two years of the program’s operation, reinsurance accounted for more than 80 percent of claims-paying capacity, while the program’s own funds (reserves) were almost negligible. By the end of 2004, the level of reserves had risen to almost 12 percent, while reinsurance accounted for 67 percent; the World Bank contingent capital facility covered the balance.

In the case of the TCIP, the PML is defined as the largest likely loss to insured dwellings from an earthquake with a 150-year return period. Under this definition, the annual probability of losses from any single catastrophic event exceeding the given PML estimate would be equal to 0.66 percent.

Buildings and units subject to compulsory earthquake insurance are as follows:

• Independent units falling under the scope of Law 634 on flat ownership.

• Buildings constructed as dwellings on lands subject to private ownership and registered in the deed.

• Independent units within these buildings used for commercial, office, and similar purposes.

• Dwellings constructed by the state, with credits provided by the state after natural disasters, or both.

The following buildings are not included within the scope of the compulsory earthquake insurance:

Buildings owned by public establishments and institutions.

Buildings constructed within the settlement areas of villages.

Buildings used entirely for commercial and industrial purposes.

Buildings constructed after December 27, 1999, without any construction license granted within the framework of the relevant regulations.

Owners of commercial and public buildings are not required to buy earthquake insurance, but they can voluntarily purchase it from private companies. The provision to exclude government-owned residential buildings from the scope of coverage is being revised to ensure that these buildings are included in the program.

Because homeowners living in villages typically have low incomes, insurance coverage in rural areas would be difficult to provide. Moreover, the government had not envisioned compulsory insurance coverage in villages, which frequently have no municipality and thus no building inspection system. Therefore, dwellings in rural settlements remain eligible for direct government support.

Because the TCIP is a tool for promoting construction of safe housing through compliance with building codes and construction standards, it cannot insure recently built buildings that do not comply with building codes.

Under the TCIP, all material damage to insured buildings (including damage to the foundations, main walls, combined walls that separate independent units, ceilings and floors, stairs, landings and platforms, corridors, roofs, and chimneys) caused directly by an earthquake (including fires, explosions, and landslides following an earthquake) are covered up to the insured value. The following risks are excluded from the cover:

• Cost of debris removal, loss of profit, business interruption, alternative residence and business office expenses, third-party liabilities and the like, and any other indirect losses.

• All kinds of movables, goods, and the like.

• All bodily damages, including death.

• Request for moral indemnities.

The type of building or unit to be insured. Buildings are classified under three categories:

o Steel reinforced concrete (buildings with steel or reinforced concrete).

o Stone and brick (non-carcass buildings, carrying walls made of materials such as rubble, bricks, or concrete with or without holes and upholsters, floors, stairs and ceilings of concrete or reinforced concrete).

o Other (wood, adobe, or other buildings that cannot be classified under the above groups).

• Earthquake zones. As was shown in figure 2.4, the Ministry of Public Work and Settlement has identified earthquake hazard zones in Turkey. These zones reflect seismic activity, faults, and earthquake history and range from level 1 (highest potential hazard) to level 5 (lowest).

• Sum insured. This sum is equal to the square meter of the dwelling multiplied by the square-meter value indicated in the Compulsory Earthquake Insurance Tariff and Instructions published by the Treasury Undersecretariat.The sum is adjusted to reflect construction costs. The maximum amount of cover for a dwelling is TL 85 billion (approximately $62,500).

Rates to be applied to the sum insured are detailed as previous (table 2.4). The program has 15 rating categories as determined by 3 types of construction and 5 earthquake zones. Although a larger number of rating categories might have been more technically accurate, the main philosophy underlying the TCIP policy has been to provide coverage on terms that can be easily understood by the majority of homeowners.

Engineering surveys of units and buildings for which TCIP coverage is requested are not possible because of the large number of potentially insurable units (over two million). Moreover, such an underwriting procedure would have been costly and thus would have made the TCIP premium less affordable for Turkish homeowners. Thus, in pricing and underwriting the business, the TCIP has to rely on the portfolio approach typically practiced by reinsurers of catastrophic risk.

The TCIP policy is a “first-loss” contract—that is, losses are to be paid after applying a 2 percent deductible but without any underinsurance penalties up to the sum insured. Losses occurring within consecutive 72 hours are attributed to a single event.

Because insurance penetration grew mainly in earthquake zones 1 and 3, the TCIP decided in the second year to boost sales in less disaster-prone areas by increasing the commissions payable to insurance companies for policies sold outside zones 1 and 2. As of March 2005, TCIP had paid insurance companies a commission of 12.5 percent of the policy premium in Istanbul and 17.5 percent outside Istanbul and zones 1 and 2.

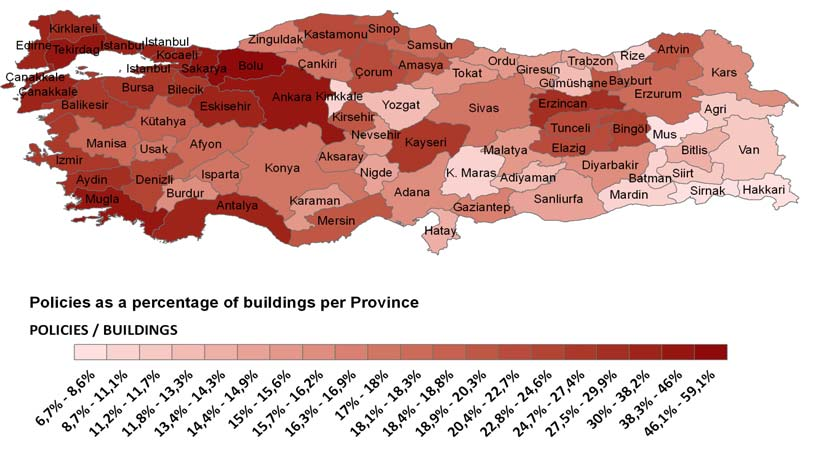

Table 3.1 shows the distribution of the TCIP portfolio by regions since the program’s establishment. The current TCIP portfolio remains unbalanced; more than 50 percent of the insured dwellings are located in the highly seismic and vulnerable Marmara region (zone 1).

Policies in force reached their highest level in 2001 at 2,430,000, representing 18.7 percent of total insurable dwellings. However, after this peak, the number dropped due to Turkey’s worsening economic situation and the public’s realization that no penalties would be imposed for non-compliance with the requirement for mandatory earthquake insurance coverage. As of September 2005, the total policy number was approximately 2.22 million, a penetration rate of about 17 percent, which represents a slight increase from the 16.5 percent figure recorded in February 2005 (table 3.2).

Affected homeowners can notify the TCIP of their claims through ordinary mail, electronic mail, facsimile, direct phone lines, and the operational manager’s call centre, where staff from different departments have been trained to receive claim notices and enter them in the computer records. This is somehow a clear difference with Spanish consorcio de compensacion de seguros. The Spanish pool claims-paying logistics uses the private market to settle and pay extraordinary risk insurance claims.

Management of TCIP assets is based on principles set out in investment guidelines proposed by the board and approved by the Treasury. In 2003 the pool retained a professional investment advisor to manage its surplus funds in accordance with its investment guidelines. Because the composition of the TCIP’s investment portfolio is crucial to the program’s ability to pay claims quickly and in full, investment choices should be immune to a loss in value in the event of a large earthquake—the time at which the TCIP would be selling assets to meets its claims.

Investments are chosen to meet liquidity, preservation of principal, and rate of return criteria. The TCIP Operational Manager chooses investment instruments in accordance with the asset allocation guidelines approved by the GDI (term deposit in Turkish lira, treasury bonds, securities) and the investment strategy based on prevailing market conditions. For domestic holdings, the credit rating must be the highest available in Turkey. The investment grade of all securities in the portfolio must be at least an A according to the Standard & Poor’s classification. Total investment exposure to one single issuer must not exceed 10 percent of total portfolio assets (except for treasury bonds). The maturity of instruments other than treasury bonds and government bonds should not exceed 181 days.

source: Insurance in Turkey - World Bank

oec.world/en/profile/country/tur

Comentarios