Financial vulnerabilities - Natural disasters

- CATRisk Consultants

- 14 nov 2020

- 7 Min. de lectura

Actualizado: 31 dic 2020

INSURANCE & REINSURANCE RISK FINANCING

The United Nations estimates that global growth slowed to a 10-year low of 2.3 per cent in 2019. A modest acceleration is expected going forward, with average world gross product growth projected at 2.5 per cent in 2020 and 2.7 per cent in 2021.

Without decisive policy action on multiple fronts, a significant and prolonged downturn in global economic activity is a distinct possibility. Amid concerns over the unintended effects of overstretched monetary policies, there are growing calls for a more balanced policy mix—one that includes a more active role for fiscal policies in supporting growth. Policymakers also need to remain focused on advancing structural reforms that strengthen economic resilience and boost long-term development prospects.

Key priorities include climate change adaption strategies, policies to accelerate the energy transition, reforms of labour markets and pension systems, investments in infrastructure and education, and measures to promote economic diversification.

That is why it is important to continue keeping the climate crisis at the top of the international agenda. The report stresses that investors underestimate the risks of climate change and are still making decisions to expand investment into carbon-intensive assets. One of the primary ways to break the link between greenhouse gas emissions and economic activity is to change the energy supply mix, transitioning from fossil fuels to renewable sources of energy. This transition will require policies that steer nations towards carbon neutrality by 2050, including setting a meaningful price on carbon pollution, abandoning fossil fuel subsidies and ending investment in and construction of coal-fired power plants.

Well-balanced policy strategies should maintain economic stability while broadening access to clean, affordable and reliable energy.

Global debt and financial vulnerabilities

High indebtedness is a key feature of the global economy, with global debt more than four times world gross product (UNCTAD, 2019b). Debt expansion has been most pronounced in the non-financial corporate sectors and to a lesser extent in government sectors. In developing countries, total debt reached about 190 per cent of GDP in 2017.

Overvaluation and leveraged loans in the United States

Share buy-backs have played a prominent role in boosting equity valuations. In the current challenging environment, stock markets are prone to sudden and large corrections amid a widespread deterioration in sentiment, with significant spill overs to economic activity. The rise of leveraged loans in the United States represents another source of vulnerability and a potential risk for financial stability. The leveraged loan market is about $1.2 trillion, more than double the size of a decade ago and larger than the high yield corporate bond market. The rise in leveraged loans has been facilitated by abundant financial liquidity, the search for yield, and the increase in securitization through collateralized loan obligations (CLOs), where payments from multiple firms are pooled together and then sold to investors in tranches. Highly indebted firms have also favoured this type of financing, which is more flexible than bonds and easy to repay. This type of syndicated loans at floating interest rates given to firms that have relatively high levels of debt relative to earnings & poor credit standards are diametrically opposite to risk pooling in the Insurance and Reinsurance industry, or government pools where hedging is not permitted and companies must take share in the risks assumed by means of technical and solvency provisions.

The amount of fixed-income securities with negative yields reached a record high in the third quarter of 2019; in September, the amount of bonds with negative yields rose to $15 trillion (see figure I.30), with about 50 per cent denominated in euros and 40 per cent in yen (BIS, 2019b). While sovereign bonds High debt levels could create a cycle in an economic slowdown.

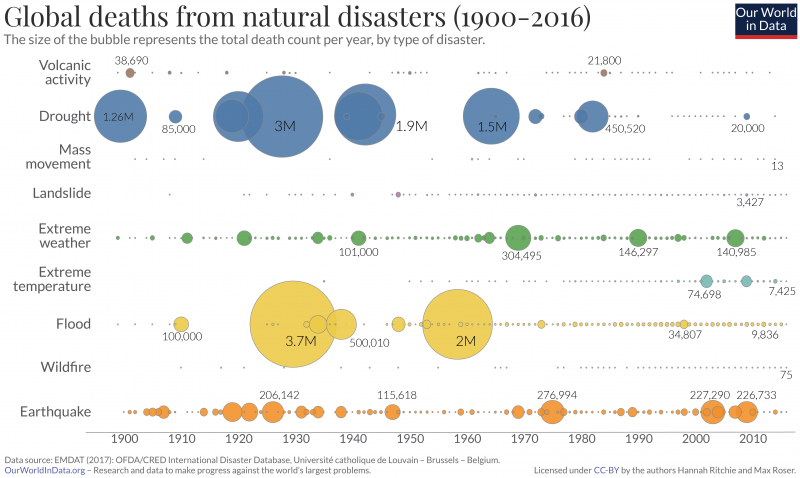

Natural disasters have significant and long-term economic effects, including loss of income, destruction of physical and human capital, and widening inequalities. Infrastructure disruptions may impact the provision of electricity, water and fuel, creating health and safety emergencies.

Financial markets continue to underestimate climate risks, including the potential damage of weather-related shocks, costs of adaptation and mitigation efforts, and risks associated with new regulations and shifting demand patterns for carbon intensive products.

As climate change becomes more a present (rather than a future) concern, insurance companies are rethinking climate risks. After years of focusing mainly on loss events such as earthquakes and tropical cyclones (so-called primary perils), which are well-monitored by catastrophe models, insurers are increasingly focused on what they term “secondary perils” such as wildfires, storms, flash floods and hail, which are often triggered by primary perils. In the past decade, average insured losses caused by secondary perils were almost double those from primary perils—a dramatic change in comparison with earlier decades. Globally, insured losses tend to account for less than half of total losses, as insurance penetration is low in many developing regions that are heavily exposed to risks, exacerbating global inequalities.

It is also crucial that nations individually and collectively review their progress towards achieving climate resilience on a regular basis and upgrade climate action plans as needed, as current temperature scenarios show that the world is far off track in meeting the target specified in the Paris Agreement.

1. Natural disasters are emerging as a macro-critical risk in many economies, especially in small, low-income, and other disaster-vulnerable states. While many developed and emerging markets rightly focus on addressing climate change, most disaster-vulnerable states are faced with the urgency of adapting to the increased strength and frequency of climate-related disasters. Therefore, focus has increasingly been on preparedness.

Such efforts have focused on:

(i) reducing exposure to disaster risk through more resilient infrastructure;

(ii) transferring risk through insurance; or

(iii) managing retained risk through self-insurance or national pools and contingency financing.

2. This note focuses on natural disaster insurance as one tool for managing the financial costs of economic disasters. Insurance against natural disasters does not reduce the physical losses following events, but it helps better manage and mitigate their financial and economic costs. Spreading the expected and potentially large one-off costs of disasters through smaller annual payment of insurance premium reduces the volatility of financial losses and can help policymakers easily manage consequences of socio-economic disasters. Disaster insurance by the public-private sector also helps mitigate the macroeconomic implications of major natural disasters for households and businesses. Recent estimates suggest that while uninsured losses account for the strong negative effects of disasters on economic activity, well insured disasters can be inconsequential for growth (e.g. BIS, 2012).

3. Catastrophe economic losses must be analysed through different risk-transfer options based on impact on debt and growth under stochastic simulations of natural and economic disasters. Disaster shocks from model-based probability distributions of disasters of various strengths, as well as estimates of their economic and fiscal costs used by the insurance industry. We then compare debt and output dynamics under a scenario without insurance (where disaster costs are financed ex-post through borrowing) with debt and output paths under alternative insurance packages, using the same disaster shocks.

4. In smaller and more vulnerable countries, natural disasters carry a higher social cost and therefore government’s risk aversion and the benefits of insurance are higher; however, the cost of significant insurance coverage is higher as well, often resulting in suboptimal insurance choices. Support from the international community can help loosen the fiscal constraints countries face in choosing the optimal level of insurance protection and help increase risk transfer with enhanced growth outcomes.

5. In larger states, damages from natural disasters are localized and therefore represent a relatively small share of the economy. In smaller countries, states or territories, natural disasters present a systemic risk, as the bulk of their territory could be affected at the same time.

6. Highly exposed countries—many with shallow or weak financial and insurance systems—can also face the problem of missing natural disaster risk markets. In such cases, risks would not be underwritten at any price due to their catastrophic and correlated nature across the local economy. This has been the rationale for government intervention in insurance markets (e.g. public underwriting of private risk pools) in many larger exposed countries. In smaller countries, the missing markets problem was solved through the creation of regional insurance pools with support from the World Bank.

The energy sector accounts for about three quarters of global GHG emissions and will play a crucial role in determining the success of worldwide efforts in climate change.

Even with improvements in efficiency, global demand for energy will continue to rise in the coming decades. Changing the global energy mix to move from burning fossil fuels is decisive for a healthy economic activity and GHG emissions. Energy transition continues and policy instruments are necessary towards disincentivizing fossil-fuel industries. Leaving many investors and Governments exposed to sudden losses and macroeconomic instability but adding efforts to achieve environmental targets.

The urgent need for a cleaner energy mix must be balanced against the equally urgent need to meet the rising energy demands of a growing population and deliver affordable energy to all.

Energy gaps, the energy mix and greenhouse gas emissions

Far more rapid progress must be made to reduce the level of GHG emissions associated with economic activity and energy use. Evidence such as historical temperature data indicates a worrying trend. In numerous geographic areas, the hottest years in the past century have occurred over the past decade. At the global level, the past four years have been the hottest in the past 139 years (NOAA, National Centers for Environmental Information, 2019).

The world is already 1°C warmer than pre-industrial levels and, as the effects of this change become increasingly felt, a global consensus is emerging around the urgent need to dramatically reduce anthropogenic emissions of CO₂, methane (CH4) and other GHGs.

In 2015, 196 countries signed the Paris Agreement and committed to the internationally agreed goal of limiting the global average temperature increase. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), there are only 10 years left to make the changes needed if there is to be a reasonable chance of limiting global warming to a maximum of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. Beyond this, even half a degree Celsius will substantially increase the risks of drought, floods, extreme heat and poverty for hundreds of millions of people (IPCC, 2018). Many coastal regions and small island developing States (SIDS) are particularly exposed to these changes.

The world is already experiencing weather-related natural catastrophes that are more severe in terms of both magnitude and frequency.

At the same time, there is a need to meet the ever-increasing global demand for energy. Based on current announced policies, without more rapid gains in energy efficiency and conservation, global energy demand is projected to grow by about 1 per cent a year until 2040 (IEA, 2019b, Stated Policies Scenario). The bulk of rising energy demand will originate from developing countries owing to stronger economic growth as living standards converge towards those in developed economies, increased access to marketed energy, and rapid population growth and urbanization in some regions. Since 2000, electricity demand in developing economies has nearly tripled as a result of industrialization, middle-class growth and expanded access to electricity.

More than half of the projected increase in global energy use is likely to originate from China, India and other Asian countries, driven by strong growth in their energy-intensive industrial sectors.

image World GDP

CO2 emissions from the combustion of fossil fuels account for over 65 per cent of global GHG emissions.

Fuentes: https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/wp-content/uploads/sites/45/WESP2020_FullReport.pdf

SOVEREIGN CATASTROPHE RISK POOLS World Bank Group

Comentarios